Interview with Steven Seagal

Insight on Aikido Question:The interview actually is two separate articles, and was originally published in two separate issues of "Off The Matt," the newsletter from Steven Seagal's Tenshin Bugei Gakuen - partially in the Fall of 1990, and the balance in the Fall of 1991.

Credits go to: Janet Pyle - Founding Editor, Original Concept and Design, Layout and Graphics, Interviewer Juan Carlos Gonzalez - Assistant to the Editor, Senior Editing Consultant, Interviewer Brian Jamison - Senior Graphics and Layout 1991-4 Shaun Ravens - Managing Editor, 1990, Editor In Chief, Graphics, Photographer and Interviewer 1991-1995 Mino Osaka - Translator, 1990-97, Editor in Chief, 1995-7 Chuck Holland - Senior Graphics and Layout 1994-7 John Spezzano, David Bunnell - Photographer 1991-3 Matsuoka Sensei - Senior Technical Advisor on all issues, Translator Mark Greenfeld, Christie Beyer, Garth McLean, Staff Assistants Nobuko Takei, Miho Tsujimura, Yumiko Okamoto - Translator.

What is Aikido? Sensei: Got a couple of years? Aikido in the advanced stages becomes much more complicated. It's theoretically based on harmony rather than blocking, kicking and punching. We allow the other person to attack and use his own attack against him by becoming one with his movement and utilizing anatomical weak points, joint blocks and throws, etc. In a life and death situation the harder the technique becomes. Often times, the attacker creates the life and death situation, because the harder they come the harder they fall. These techniques will work on anybody but you really have to learn them. Aikido is not a quick art to learn.

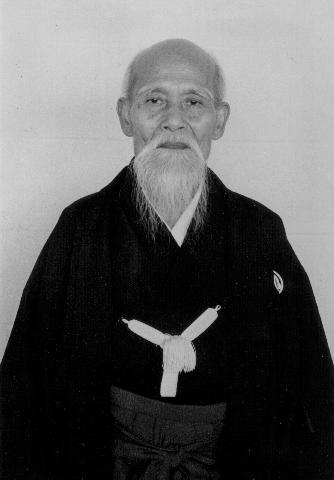

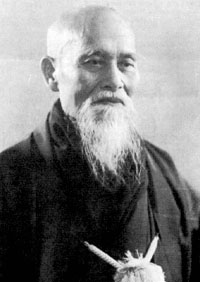

Q: Why did you study Aikido instead of karate? Sensei:I started in karate and was in search of a teacher who could teach me the mystical aspects of the martial arts. The people I studied with in karate didn't give that to me. I found Aikido and read some of O-Sensei's speeches and saw him.

Q: What master(s) did you study under? Sensei: I was in and out of Japan as a youth and saw Tohei Sensei when he was still with Hombu Dojo. I studied with numerous teachers who you don't know and never heard of; from Isoyama Sensei to Abe Sensei. Just a bunch of people most of who are dead.

Q: Was there ever a critical point in your training career where you made a dramatic change? Sensei: Yes, for six years I practiced about eight hours a day, that's a lot, in Japan. I was beating my head against the wall and I was making no progress. I wanted to transcend the physical aspects of Aikido. I was trying to do some of the things 0-Sensei was doing but I was getting nowhere because I was trying,. Finally one day, I went out into Kameoka in Ayabe province and started training with some of 0-Sensei's mystical teachers and started spending more time on the mystical aspects of Aikido. I experienced tremendous and dramatic changes in my technique in the first six months.

Q:Why didn't more of 0-Sensei's students find the mystical aspects of the technique interesting or important? Sensei: 0-Sensei had a real old dialect named Tanabe. There's this place way up in the mountains, its a country area with a dialect, that's really hard to understand. I would talk to the other guys and I'd ask them what he was saying. They would say, "ah, he's talking about God and religion and that crap, forget about that and learn how to fight." That was the attitude. Yet, when I went up and studied with some of the same priests that taught 0Sensei, I began to understand Aikido for the first time in my life. Because Aikido is more than waza.

Q: Have any of 0-Sensei's mystical teachings been translated into English? Sensei: 0-Sensei was a priest in a sect called Omotekyo. They have some stuff in English, but I don't think you can get it in the United States, sorry

Q:I've heard a lot about hard-line and soft-line Aikido, can you touch upon what the difference is? Sensei: 0- Sensei always talked about Go-ju-ryu, the circle, the square and the triangle. Aikido has to have all of these lines together. The basic movements are square, very square. When you get to the intermediate level, the square is always there but you see a lot of the triangle. When you get into the advanced level you see mostly the circle. But the square is always there.

Q:Do you ever use Ki-ai in your techniques? I don't think I've ever heard it from you. Sensei: You won't want to. Ki-ai is very effective and when you do it right you'll paralyze your opponent.

Q: Is there a correct position to start? Sensei: When somebody comes up and they're going to do something, you stand how ever is comfortable and you do what you have to do. The idea is if I am in left hanmi and somebody comes at me, he probably won't come at me in right hanmi because his face is going to be in your fist. However, you never know, the idea in the street is to empty yourself and let it come.

Q: In terms of technique what would you say is the most important? Sensei: I would say "irimi" is the most important.

Q: In Aikido is it just practising to fight, or life and death situations? Sensei: The difference between a real fight and sparring on the mat is the difference between swimming in the ocean and swimming on the mat.

Q: Is a technique based upon someone fully advancing and fully committing their body weight to you? Sensei: Yes. In basic, beginning Aikido. But in advanced Aikido it doesn't matter.

Q: Not even with a punch like a boxer would punch? Sensei: Not at all. It doesn't matter if they stay, if they run from me, if they stand there and do jumping jacks If I think I have to terminate a situation or neutralize a situation, I'm going to go after you. That is advanced Aikido. I don't need you to move. You can punch at me, you can do whatever you want.

Q: Then Aikido can be aggressive? Sensei: Let me tell you a secret, those who practiced with 0-Sensei, whenever they attacked him, they were afraid the'y were going to die. Ask my advanced black belts if they find it a piece of cake when they attack me. It is not a cake walk. For example, I'm in a restaurant and somebody pulls a gun and holds a bunch of people hostage. If I don't have a gun, I'm not going to wait for him to try and pistol whip me. I have to do something then, I have to know techniques where I can go to him, and that is what "irimi" is all about. Covering space from here to there as quick as I can with irimi. That is any one of a number of techniques. If you do them quick enough and your opponent doesn't move with it, they become strikes. Because they're going to hit and they're going to hit hard. if your opponent doesn't understand how to move with them, they're going to get hit in the real world.

Q: How can a disabled student get involved in the martial arts? Sensei: It would depend on how disabled they are and which way they are disabled. If you have the use of your hands and your arms, then you can do Aikido almost the same as I can. The concept is that somebody must come to you. Once they come to you, the hand movements, the movements of the torso, and everything else are the same. In a lot of ways you can become a very good Aikidoist. I know that during the times I got hurt very badly I learned my technique properly was because I couldn't move.

Q: Can people that are 55 or 65 practice Aikido? Sensei: I've had people in their 70's train in Japan and in their 60's and 70's train here.

Q: Could you explain zanshin and mushin? Sensei: In the martial arts there are many concepts. I could write a book, I could spend the next several hours on these subjects. They are not something I would even attempt to talk about in 5 minutes, but I will take a second to talk about "mushin" because I mentioned it earlier. Mushin means empty heart, empty mind. Its very, very important in the martial arts. When Yagyu Tajimano Kami and different great mushin masters talk about this concept, they talk about the perfect and accurate reflection of all that is. I've taught courses on this. Its a very long story. One analogy is: the reflection of the moon on a placid Lake.When the moon breaks through the clouds, when the wind blows, the lake gets ripples in it the image of the moon gets distorted. Likening this to your mind and your heart. When you have thoughts in your mind and your heart, everything is distorted. In order to become one so that you can understand everything and sense everything the way it really is... you have to be completely-empty; completely calm. That is mushin.

Q:What is the relationship between Budo and Aikido? Sensei: They are the same.

Q:There's some confusion because there's a wide range of attitudes towards Aikido, from a very soft martial art to a killing martial art. Sensei: I think those are just silly aberrations. I think Bugei, if you look, Budo, if you look at the original Chinese calligraphy and you break it down, it means to stop war. Stop arms, stop war. So Budoka is a heihoka ,a warrior is really a warrior for peace, or a man of peace. You have to be powerful enough to stop war, you see what I am saying, because if you're weak you can't stop war, you get warred upon. You understand? And Budo has that yin and yang, it has that Tate to yoko no ito, izu no mitama to mizu no mitama. These are all Shinto terms. Yoko no ito means moon, feminine, water, love, the power of forgiveness, the power of love. Tate no ito means sun, we talk about masculine, we talk about fire, we talk about the power of decision. That is the time when you don't forgive, that is the power to cut. Those two elements have to live our within you in perfect harmony or you're out of balance, and that is the to murder your essence of Budo too. You have to have the ability and capability to decide to make decisions,to cut,to kill,and at the same time,you have to have the ability to love,to forgive,to be understanding.And those have to work together,but Budo is all of those things and Aikido is one of the millions of martial arts under the vast umbrella of Budo,you understand?

Q: What can we as Aikido students do to improve the political situation of Aikido? Sensei: Unfortunately a lot of the teachers of Aikido are more concerned with who's better than who and who has more students. Am I wrong? In Aikido it doesn't matter who is better. It doesn't matter who's right and who's wrong, or who has how many students or whose dad is bigger than whose. Who cares? None of this matters, it has nothing to do with Aikido. What matters is that we all try to help each other to improve ourselves as human beings. Whatever styles come to us are welcome, nobody is better than anybody. Concentrate on the philosophical and the spiritual aspects of Aikido rather than who's affiliated with who.

Q:Sensei, I've been interested in Kotodama, could you explain it for us? Well, that's like trying to explain Buddhism or Christianity or any other mystical art. Kotodama would take me a couple of weeks to talk about, to where I felt comfortable. Kotodama is really the power of sound; holy sound and unholy sound. If I may use your sensei for a second, as he comes to punch me (Wada Sensei punches and Master Seagal lets go a "kiai") I do that. That is not a word, it is a sound he felt. He felt it in here (pointing to his heart) and in here (pointing to his head). Some of you felt it and some of you didn't. The power of sound can be used in a lot of different ways, but kotodama encompasses holy words and unholy words in sounds. Kotodama can be used for healing or killing, it is like any other magic, it can be used in both ways.

Q: Could you describe your focusing process on- someone when you are getting prepared for techniques? It seems like you're going through a very specific focusing process. It's a cycle. When I'm instructing, it's just their body position and my body position. When you really throw, you have to collect yourself and start to culminate energy. You'll set them up, grab their "ki", you grab them from way out and you bring them to you. When they come to you, you do what you want to do, it's like lightning. Onisaburo, who, as you know, was 0sensei's spiritual teacher, wrote the Kanji ku kaminari which means"Budo is lightning." The culmination of electricity and power between heaven and earth, that's really what bugei (the martial arts) is.

Q: How should the uke be setting up for this? The uke should not be thinking about taking anything nor thinking about doing his ukemi. He should only be thinking about attack. In the advance stages you don't even think about attack, you just attack.

Q: Could you give me your interpretation of Musubi? Sensei: Something meets to become one, its very simple.

Q: Like the relationship between uke and nage? Sensei: It can be, I can say Musubi in 15 million ways-it's like taking the word marriage in English. Musu means to become one to bring together.

Q: Would you elaborate on how you breath? Sensei: I don't breathe. (Picking someone for ukemi). I'm not going to throw him, I'm not going to do any technique. He's going too attack. (He attacks). Can you see where I stopped and started breathing? You probably can't see it. I never breath during one confrontation. When I do multiple attack with 3,4, or 5 people attacking me at the same time, I'm breathing very, very slightly between each one. This is the way I do it. I'm not saying that your sensei would do it that way.

Q: Why do you do that? Sensei: Because with me ;the epitome of my power is in a position where I am flexing and bringing everything together. Its more of an exhale: you inhale when you want to bring somebody in or grab them and once you get them you can't inhale because they can penetrate you.

Q:Sensei, I've been reading a little about the Mushin and the proper state of mind to have when fighting-not to draw back, not to draw forward, to wait to have the open mind. Are there any exercises to develop that? Sensei: I think meditation, understanding that when you become one with all things, you develop a sphere, like a mirror, that is a perfect and accurate reflection of all that is. When somebody attacks with great evil, you reflect that and their greatness will come back at them. You are not God ,but you become one with God and you allow God to be the judge of how that technique will come back at them. In other words, if somebody attacks me out on the street, I don't think to myself, "I'm going to get this guy and I'm going to kill him." I don't think at all, I just react to his specific energy and I do what I have to do. In accordance with what I've said earlier; whether I take a life or save a life, ultimately there is no difference. I would rather save a life. But if, for example, I was standing in the middle of the street and saw the "night stalker" slit someone' s throat and then he turned to kill me;my action might be to terminate him. I would feel bad about taking human life, but I don't feel it would be my decision. It would be an act of my training. Action and reaction in terms of force and levels of negativity. Does that make sense to you? I would rather be nice as I said earlier, but if I have to not be nice, I'm very prepared to do that.

Q:So what you're saying is not a question of you being nice or not nice, but of you're reflecting what is in the mirror? Sensei: That's exactly what I was trying to say.

Q:I'd like to know if you have a similar attitude in relation to healing, for people who need help? Sensei: Well, it's very different ... but similar in the sense that I don't treat too many people anymore and the only people I do treat are people I feel want to be better and have a, kind of karma with life that I can appreciate. In other words if somebody comes to me who has a bad heroin habit and thinks he wants to get better but I know he's not going to, I'm not going to treat him. if somebody in this dojo came to me' today and said, "I'm having a problem with I my ovaries and if I felt this person really wanted to get better, I would treat her. Do you see what I am saving? I look at the individual and see what I can see from them and try to work with that.

Q: And your experience with 0-sensei? Sensei: I have very little experience with 0-sensei. I was able to see him several times. I've seen him speak. I was very close to his spiritual teachers and I still am. I think I was the only white person to ever go exactly in the footsteps of 0-sensei in terms'of his mystical training. I became a priest in O'moto Kyo and went to all the aesthetic training with the priest that 0-sensei was raised with. I never really knew him. I never got to butt heads with him on the mat or was thrown around by him or anything else.

Q: I read in an article that kenjutsu is a part of your life? Sensei: Well, to me Aikido and kenjutsu are the same thing. If you've seen my technique, I'm always cutting. Today we just did a couple of stabs at this and that, but when you watch me a lot you'll see I'm always cutting with the feet and the hand; tesabaki, ashisabaki. The hand and feet angles are all kenjutsu.

Q:It seems today that your Aikido was very pragmatic; a street oriented type rather than other Aikido styles which are not as pragmatic as your style. I was wondering if you at any point explored any others avenues of Aikido? Sensei: The physical technique of Aikido at the level I'm teaching has nothing to do with the mystical applications in the way that you're referring to, i.e.,there is Go-ju-Ryu (hard, soft and flowing). Now 0-sensei always said, "Bugei wa Bugei desu." The martial arts are the martial arts. And, "Aiki wa odorijanai." He always said that Aikido is not dance. If you ever took 0-sensei's Aikido, or watched him, you'd be scared to attack him because he didn't play. As soft as he was, if you weren't there, you'd get hurt. Aikido is serious and it has to work. That is what the founder said and he was right.Aikido has to work. All I'm doing is teaching you how to make your Aikido work because it doesn't work for a lot of you. I try to teach you how to make it real. There is nothing unspiritual about that at all. In fact it's more spiritual. It's real, it's not an illusion, it's not a cartoon. You have to feel it to understand it. 0-sensei was a great mystic but his Aikido worked. There are lots of people who tried to get him on many different occasions, from before he started Aikido to long after. They found out it's no joke. And if you can't do that; if you can't walk out into that street and let a couple of gang bangers come at you with baseball bats, and know that you' re going to do the right thing, you don't know Aikido. It has to be real; otherwise take up aerobics or something. I go into some dojos and see somebody attacking and the guy falls and nobody touches anybody. Is there anybody in here who can throw anybody without touching them? You've got to make it work. I'm serious.

Q: Are you saving that some Aikido dojo's are too passive? Sensei: There are dojo's that teach that way (throwing without touching); and I think that in order to teach that way you first have to learn the basics and within the basics you have to be able to make them work. Once you've learned the basics and made them work you can get into the magical stuff that takes 20-30-40-50 years to get the feel for.

Q: How would one pursue the mystical aspects of Aikido after achieving the basics? Sensei: It would be available with me, or any other person who has that kind of mystical background. When you get close enough to your teacher, he decides if he wants to teach you.

Q: Can another religion or spirituality be just as valuable as Omoto Kyo has been to your Aikido? Sensei: I would imagine so, it certainly could be. One thing about Omoto kyo, and even 0-sensei said, that every religion says, "We are the path, any other path is wrong and you will go to hell." There is no religion that I know that doesn't say that except Omoto-kyo. We're all going up the same mountain, there might be different paths but we're all trying to get to God. Everybody has their own way to get there.

Q: What part of Aikido came from swordsmanship? Sensei: All parts, when I do nikyo, I cut. When I do irimi, I cut, shihonage, it's all kenjutsu.

Q: How old were you when you opened your dojo? Sensei: About 22. Thank you all very much.

oOo